On the 100th anniversary of the polar explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton’s death, a research mission using a fleet of underwater robots to determine the impact of Thwaites Glacier on global sea-level rise, departs from Punta Arenas, Chile (6 January 2021). A team of 32 international scientists will set sail on the U.S. National Science Foundation icebreaker Nathaniel B. Palmer bound for the remote glacier in West Antarctica.

This mission forms part of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC), a five-year, $50 million joint U.S. and U.K. mission to learn more about Thwaites Glacier, its past, and what the future may hold.

Thwaites Glacier, covering 192,000 square kilometres (74,000 square miles)—an area the size of Florida or Great Britain—is particularly susceptible to climate and ocean changes. Computer models show that over the next several decades, the glacier may lose ice rapidly, as ice retreats. Already, ice draining from Thwaites into the Amundsen Sea accounts for about four percent of global sea-level rise. A run-away collapse of the glacier would contribute around an additional 65cm (25 inches) to sea-level rise over the coming centuries.

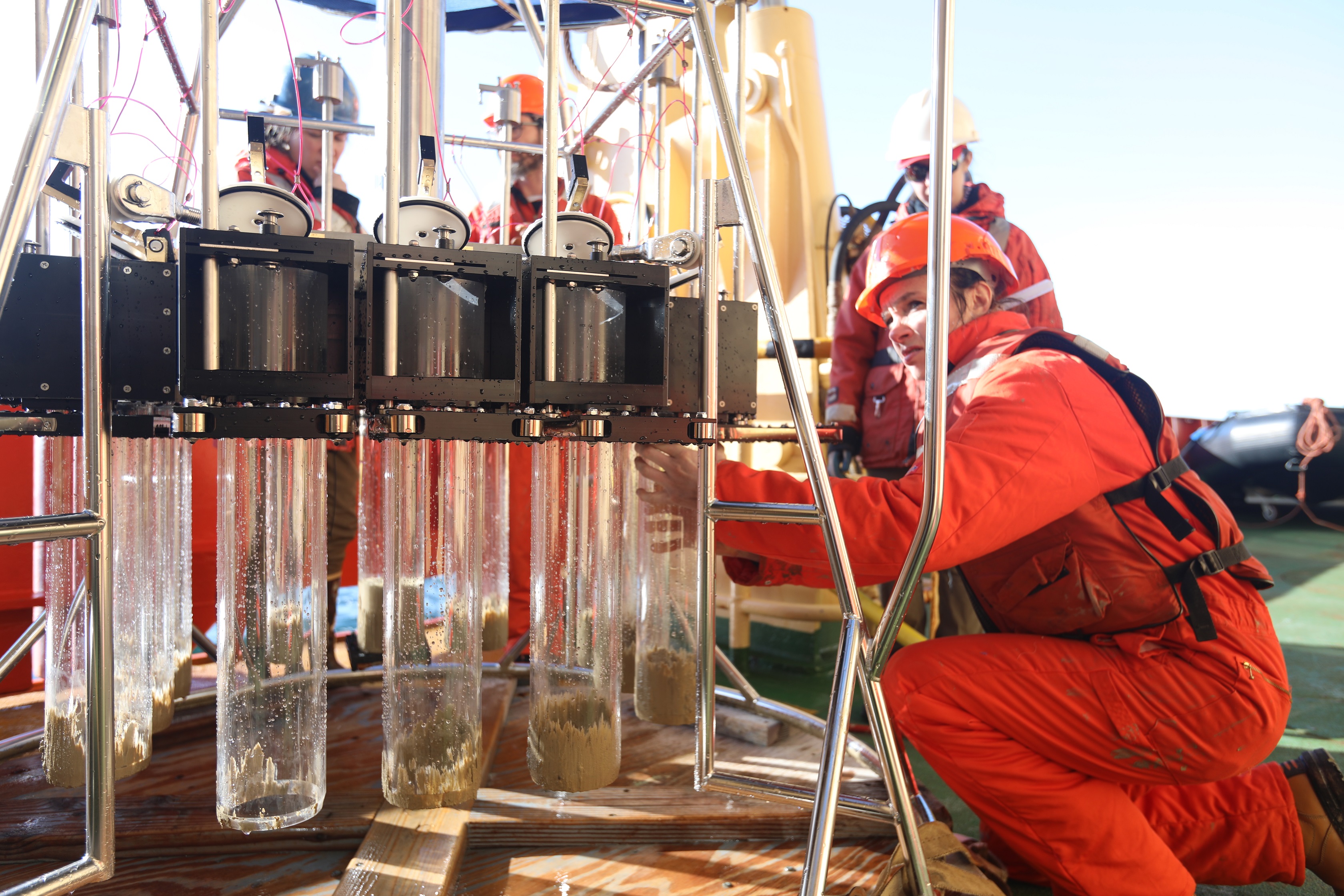

The 65-day voyage, led by scientists from the University of East Anglia (UEA), along with researchers and engineers from Sweden and the U.S., will investigate atmospheric and oceanic conditions close to Thwaites ice shelf, the floating part of Thwaites Glacier where it meets the sea. Boaty McBoatface, the state-of-the-art Autosub Long Range (ALR) vehicle operated by the National Oceanography Centre, will travel under the ice shelf along with Ran, a Hugin robot, from University of Gothenburg in Sweden, while six ocean gliders patrol the entrances and exits to the ice shelf cavity. The fleet will explore largely uncharted territory, to measure geometry and melting processes, the seafloor below, the ice thickness above and water properties in between.

Professor Karen Heywood, from UEA and U.K. lead on the ITGC TARSAN project, says: “This is a massively ambitious mission that we have been planning for several years. We will deploy two big underwater robots underneath the ice to collect detailed data from this crucial area of the glacier that will enable us to understand what will happen in the future. By measuring the ocean properties in sub-ice shelf cavities, we can understand how the ocean transports heat and what impact this may have on the glacier. I and my team back at UEA are going to be remotely piloting the six ocean gliders, smaller robots, once the scientists on board launch them into the water.”

Alongside the robot teams, scientists from University of St Andrews will tag seals to acquire ocean temperature and saltiness data around the ice shelf for the next nine months over the Antarctic winter, and researchers working on the ITGC THOR project will collect sediment cores and survey the seabed. At the same time, researchers working on the partnering ARTEMIS project will measure chemical properties of the seawater, including minute quantities of iron that are the foundation of the Antarctic marine ecosystem.

Dr Rob Hall, from UEA, is the Chief Scientist in charge of the voyage. He says: “It’s very exciting, though also daunting, to be leading this campaign to make critical measurements of the ocean under and around this vulnerable ice shelf. The team have completed a month of quarantine to ensure everyone is safe, and now we’re looking forward to putting our wide range of scientific instruments into the water to see what we will learn about how the ocean melts the ice shelf from below. We’re already monitoring the sea ice extent carefully to devise the best way to access the area, because even this powerful icebreaker ship can’t get through thick sea ice.”

Professor Anna Wåhlin from the University of Gothenburg is delighted to be onboard. She’s brought along her big underwater robot, called Ran. She says: “Ran will venture beneath the ice shelf to map what it’s like. It will collect samples of water for later analysis and map the seabed with unprecedented accuracy. An ice shelf cavity is like another planet – we just don’t know what we’re going to find when we explore it.”

Dr Alex Phillips of the National Oceanography Centre says: “Our science and engineering teams have made enormous strides in pushing the boundaries of how we explore the world’s oceans with underwater technology. Autonomous underwater vehicles are vital equipment to enable oceanic research and we’re so excited to be joining the wider ITGC team with Boaty McBoatface, which will travel further under the Thwaites Glacier than ever before. The research the ALR is supporting at Thwaites Glacier will be fantastic for the science community, marking an important change in how we collect important ocean data to understand the effects of climate change.”

TARSAN and THOR projects are two of the eight ITGC research projects, which study the entire glacier to establish the impacts of what is known to be one of the most unstable glaciers in Antarctica. In addition to those on the cruise, researchers from ITGC projects TIME and TARSAN are currently in the deep field conducting research from the surface of Thwaites Glacier, having arrived to the icy continent by plane. ITGC’s ultimate goal is to predict how much Thwaites will contribute to global sea-level rise, and how soon a transition to more rapid ice retreat might occur. ITGC is funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and U.K. Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).