New science briefing summarises results of the ambitious international collaboration to study Antarctica’s most worrying glacier

Cambridge: A vast area of the Antarctic Ice Sheet continues to retreat as a UK-US group of scientists reveal new findings about how and when it might suddenly move towards collapse.

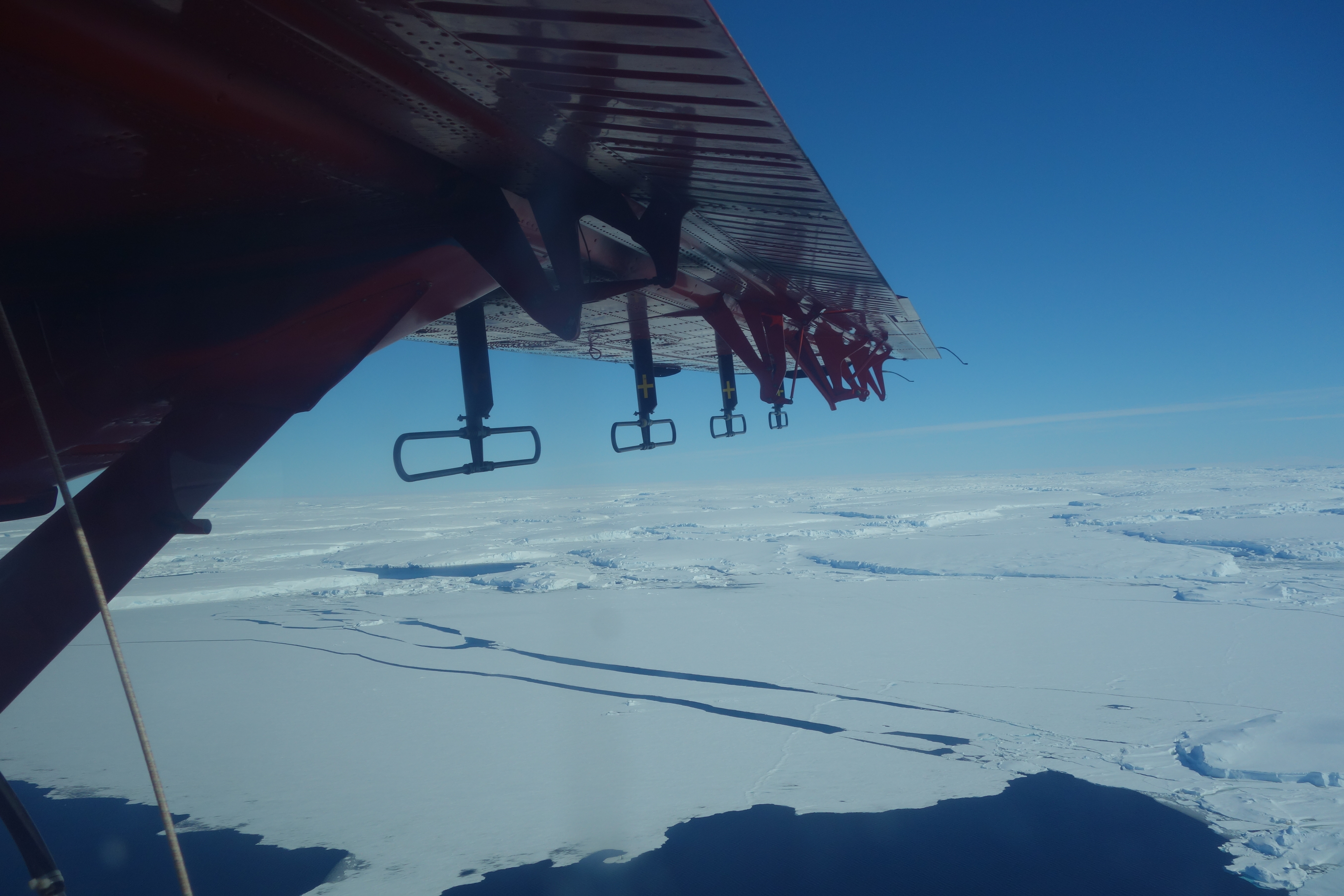

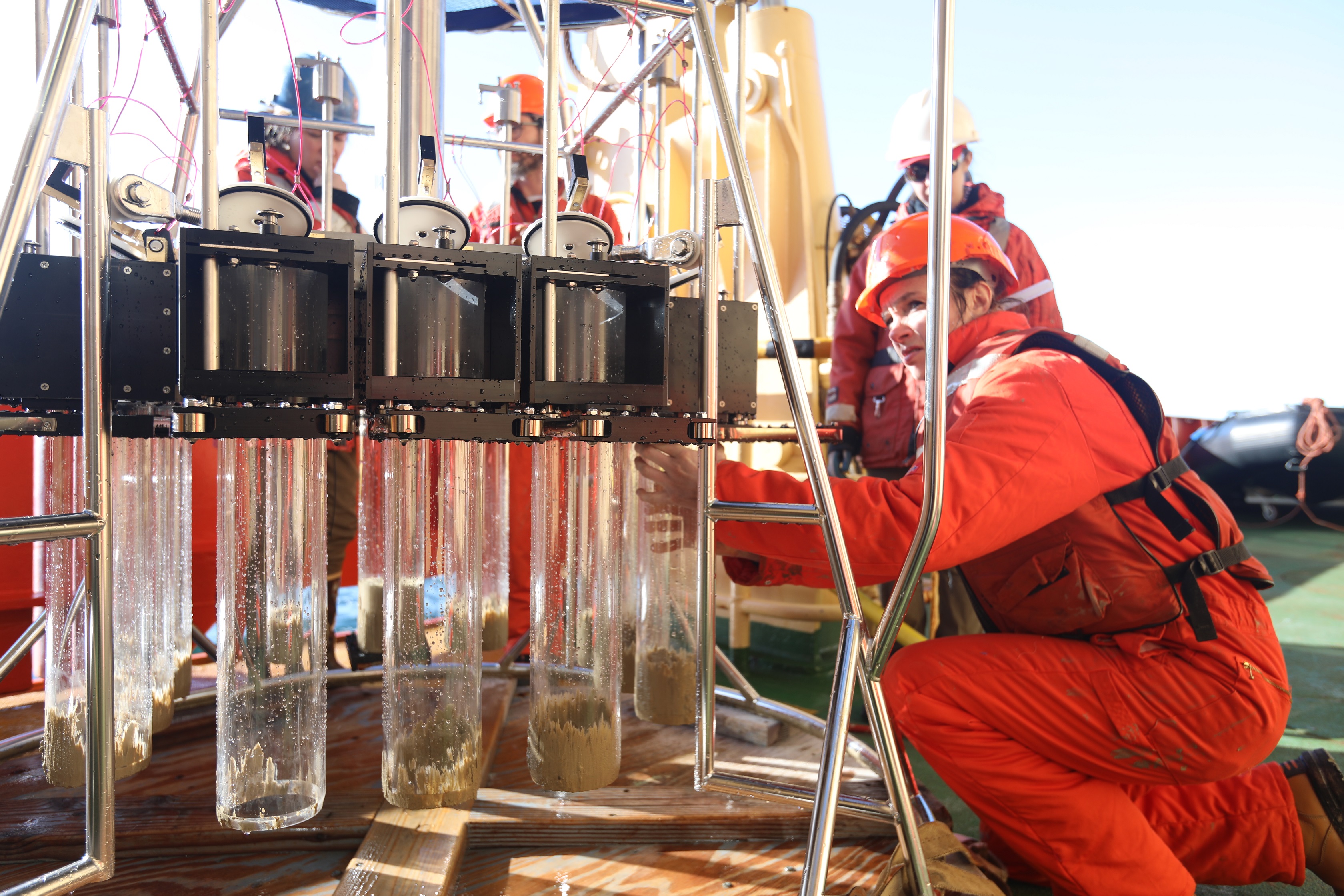

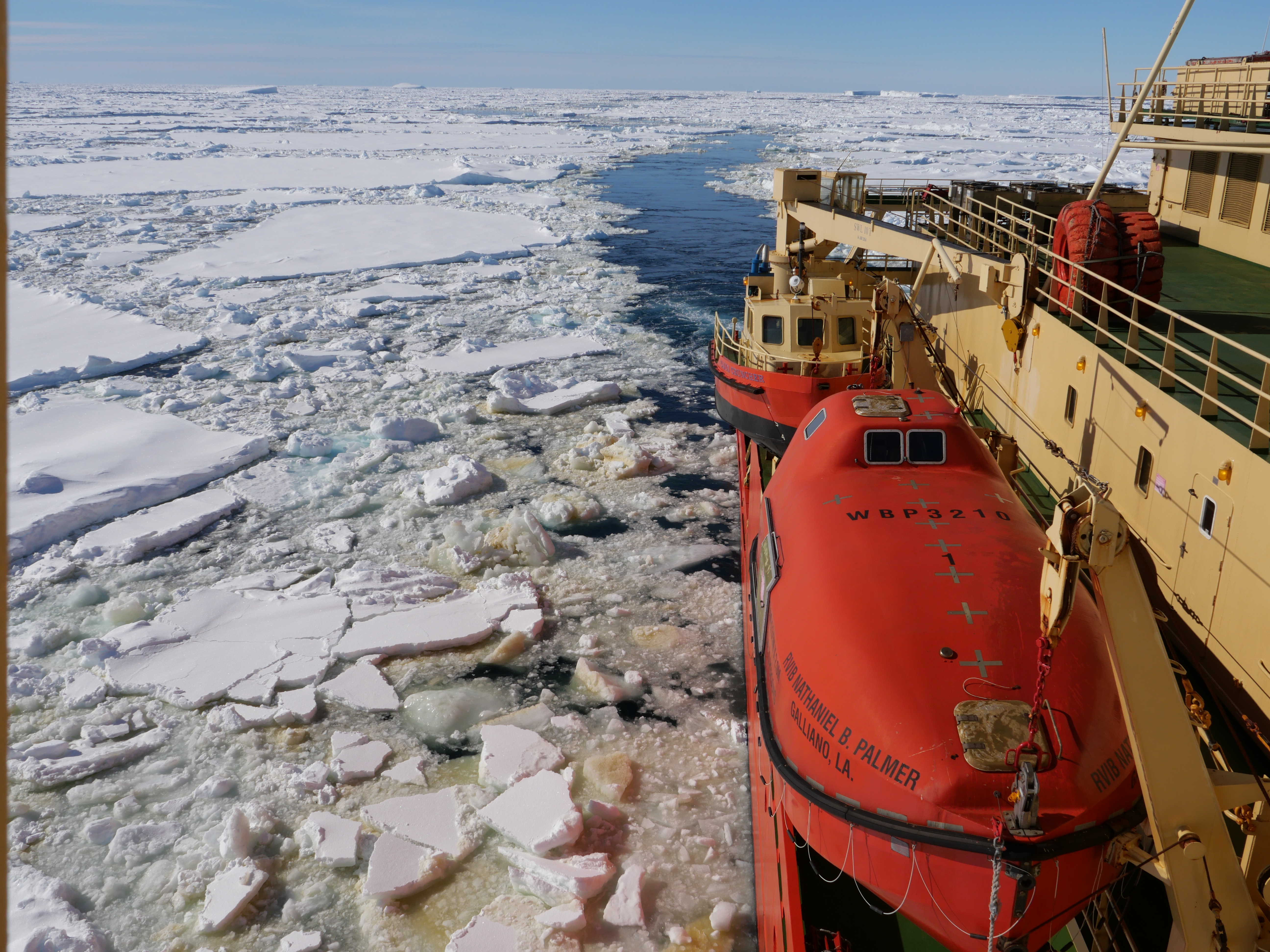

Since 2018, researchers have uncovered a complex, rapidly changing environment at the remote Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica. Scientists from the UK and US are meeting at British Antarctic Survey (BAS) in Cambridge this week (16-20 September) to discuss their observations and study results.

Prior to the start of the project, named the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC), little was known about the mechanisms controlling the retreat of this enormous glacier - one of the largest and fastest-changing glaciers in the world. If it collapsed entirely, sea levels would rise by 65 cm.

Thwaites Glacier spans an area equal to the island of Great Britain or the US state of Florida, and in places is over 2000 m (over 6,500 feet) thick. The volume of ice flowing into the sea from Thwaites and its neighbouring glaciers has more than doubled from the 1990s to the 2010s, and the wider region, called the Amundsen Sea Embayment, accounts for 8% of the current rate of global sea level rise of 4.6 mm a year.

The mission of the ITGC is to gain an understanding of the critical physical processes controlling the glacier in the present climate and over the last few thousand years, and to build a more reliable prediction of how the glacier will change in the future and why.

“Thwaites has been retreating for more than 80 years, accelerating considerably over the past 30 years, and our findings indicate it is set to retreat further and faster,” according to Dr Rob Larter from the Science Coordination of the ITGC and a marine geophysicist at BAS.

The work of ITGC is trying to predict the rate and magnitude of ongoing sea level rises that will have a huge impact on the hundreds of millions of people on coasts from Bangladesh to low-lying Pacific islands, from New York to London.

“There is a consensus that Thwaites Glacier retreat will accelerate sometime within the next century. However, there is also concern that additional processes revealed by recent studies, which are not yet well enough studied to be incorporated into large scale models, could cause retreat to accelerate sooner.”

The findings suggest Thwaites Glacier and much of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could be lost by the 23rd century. Thwaites Glacier is exceptionally vulnerable because its ice rests on a bed far below sea level that slopes downwards towards the heart of West Antarctica.

Using advanced technology such as underwater robots, novel survey techniques, and new approaches to ice flow and fracture modelling, the scientists have gained new insights into these processes. This has improved the performance of predictive computer models, but much remains to be understood about the glacier’s future.

The colossal Thwaites, at roughly 120 km across, is the widest glacier on the planet. It is also a keystone of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, much of which sits on a bed below sea level and would raise sea levels by 3.3 metres if it all melted.

“It’s concerning that the latest computer models predict continuing ice loss that will accelerate through the 22nd century and could lead to a widespread collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet in the 23rd,” according to Dr Ted Scambos, US science coordinator of the ITGC and glaciologist at the University of Colorado.

He continued, “Immediate and sustained climate intervention will have a positive effect, but a delayed one, particularly in moderating the delivery of warm deep ocean water that is the main driver of retreat.”

The ITGC is funded by the US National Science Foundation and UK Natural Environment Research Council.