Snow on Ice: When in Antarctica: the backup to the backup #8

“I think the secret to the work we do in many ways is as much as possible beforehand, asking the question, ‘what if, what if, what if.…’” Andy Smith, a principal investigator on the ITGC GHOST project, commented about working in Antarctica’s isolated and difficult outback. “You have to get used to the fact that you can have a wonderful plan on paper, and it’ll change completely when you’re actually trying to achieve it.” Looking back on our cruise, this mantra has unquestionably held true. When you work in Antarctica, you work in one of the harshest environments in the world, and definitely the most remote. That means contending with a wide range of unpredictable weather and ice conditions, medical challenges with the nearest hospital four days away, and instruments and infrastructure that take a beating or become obstinate in freezing wet conditions. The fact that we now sat with Andy at the British Antarctic Survey’s Rothera Station on the Antarctic Peninsula was testament to that.

On February 14th, we had left the Edward Islands on our way, finally, to the ice front of Thwaites Glacier. By then, we had experienced a day where we had sent our seal and geology teams to the islands and had to immediately turn around to retrieve them as winds rose to over 30 knots in less than an hour. Riding in the small boat could feel like a thorough 30-minute rinse in the washing machine, set to bitter cold and extra salty, even with your survival suit on. That left us only able to do multibeam – mapping the features on the sea floor – our contingency plan for the 20 hours we waited for winds to come back down below 20 knots. When the weather calmed, our work on the islands continued successfully in bright sunshine.

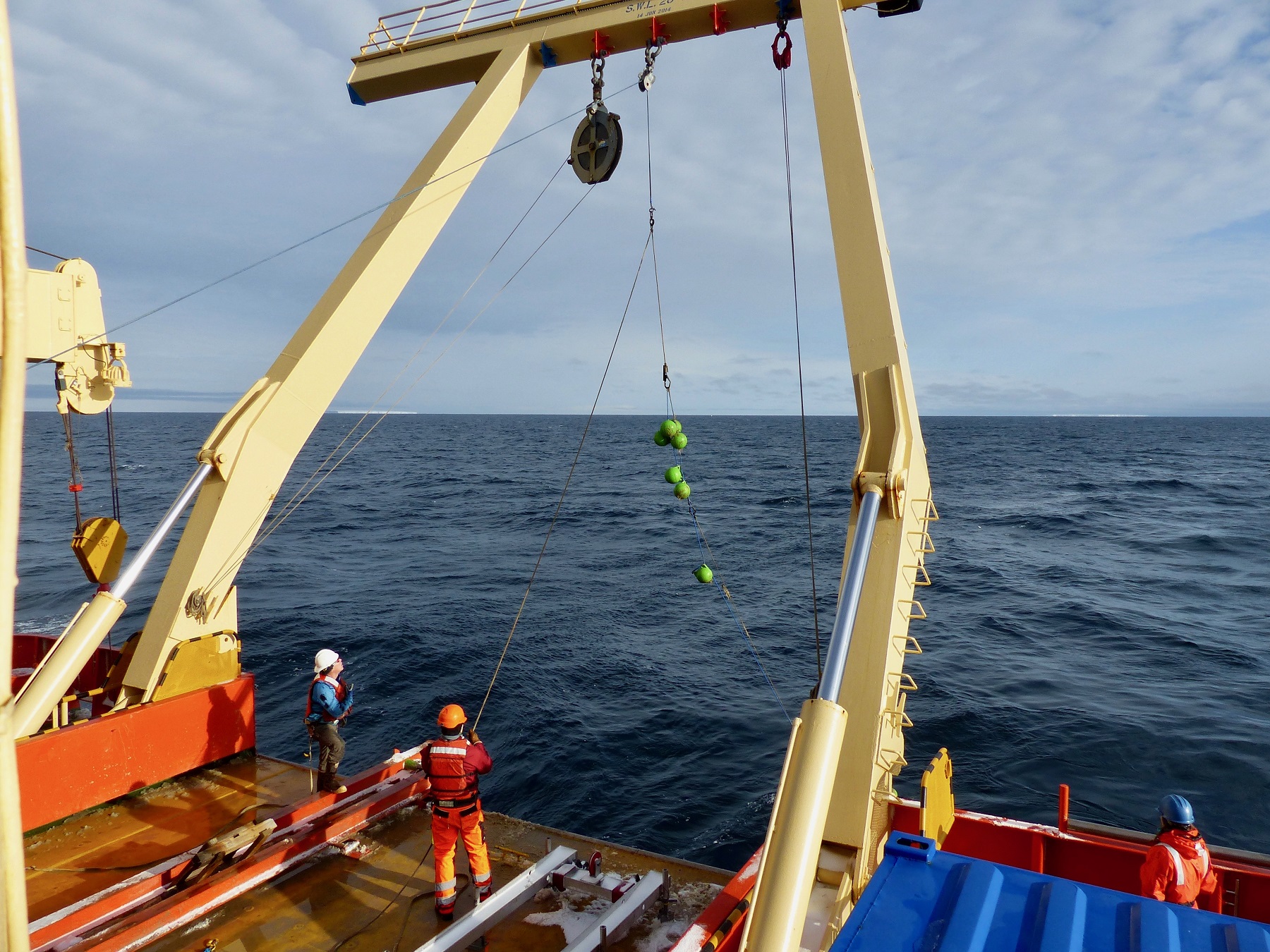

After departing the islands, we stopped to let TARSAN scientist Mark Barham from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), pull up an ocean mooring. The 400 meter (1400 foot) mooring line anchored onto the sea floor had six instruments clamped on along its length and had been recording ocean temperature, salinity, and velocity from the deep for five years, here. After the successful recovery of the gold mine of data that will soon feed many hungry ice sheet and ocean models, we headed for Thwaites.

Dangling from the yellow A-frame like a fishing line, this cluster of green floats marks the first section of the 400 m (1300 ft) mooring line pulled on deck by Jack Greenberg and Mark Barham. Released from its anchor in a deep trough 900 meters below us, it carries six instruments attached at multiple depths along the line. The mooring was anchored for five years, and its recovery brings years of ocean temperature, salinity, and velocity measurements to scientists. Photo credit: Tasha Snow

Eight hours from our destination, though, we got the word. The ship needed to run a medevac (stands for medical evacuation) for someone onboard. While the person was stable, they needed medical attention that could only be found at a hospital, the closest being in Punta Arenas, Chile. We needed to head to Rothera Station, a four-day journey at top cruising speed (13 knots) out of the Amundsen Sea and over to the Antarctic Peninsula. From there, the individual would take a quick flight north to Punta Arenas.

Steep mountains with glaciers spanning between them stand in the background rimming Ryder Bay next to the British Antarctic Survey's Rothera Station. Cranes sit near the waterfront along the airplane runway, steadily working on major renovations for the base that are expected to be completed in 2020. Photo credit: Aleksandra Mazur

So there we were at Rothera, an unexpected destination on the cruise, but one that worked out to be an incredible addition. Marguerite Bay, leading up to the station, sat surrounded by jagged towering mountains, snow-covered and draped with stunning smooth-topped glaciers that ran between the peaks like winding, amusement park slides. Sharp black volcanic rock peeked through in areas where snow had melted from the steep mountain slopes. Rothera Station sat cradled at the edge of the water, almost unnoticeable from afar amongst the goliaths around it -- despite the large construction cranes renovating its waterfront. Needless to say, it wasn’t a bad place to wait for a day or two if you had to.

Rothera serves as a waypoint for many scientists going in and out of Antarctica, and all of them had experienced the familiar Antarctic setbacks to research. To our luck, Andy Smith and Carl Robinson were two of its present visitors, on their way out of the field to head home. Andy had just returned from a non-ITGC research project on the Rutford Ice Stream. His work in the ITGC GHOST project will peer into the inner layers of the ice of Thwaites Glacier and the rock below. Doing similar work this season at Rutford as will be done at Thwaites during the 2020 field season, his group used hot-water drilling to place instruments in the ice and conduct seismic work, mapping the shape of the landscape and the types of rocks found below the ice sheet. Some of Andy’s research uses small explosives paired with geophones (a.k.a. seismic detectors) that do the equivalent of earthquake detection on the ice. The explosives produce sound that travels through the ice and into the rock below, some of it bouncing back to the detectors along the way. The travel time of those reflections can be equated to distance for producing maps, based on the properties of the ice and rock and how sound travels through it. Is the bed made of hard, jagged bedrock that is difficult for ice to slide over? Or is it soft, smooth, and easily erodible sediment that allows the ice to move over it more rapidly? The underlying bed is not well-understood at Thwaites, but has been shown at other glaciers to play a significant role in controlling spatial patterns of ice flow. What they find at Thwaites will be used in ice sheet models and, from there, could tell the ITGC group whether we can expect a run-away glacier with more melting, or some kind of stabilization before the worst scenarios may come to pass.

Researcher Andy Smith (left), explains the geophysics work that will be conducted at Thwaites in the 2020 season for the GHOST research project. He has just returned from Rutford Ice Stream and explains to Carolyn Beeler (right), a journalist onboard the Palmer, that work in the field demands us to ask, "what if, what if, what if..." for all of the setbacks that might arise in Antarctica. Photo credit: Linda Welzenbach

I asked Andy whether the setbacks we had been experiencing on the Palmer were typical with his Antarctic work. “You just have to get used to making the best plan as you can, making as much contingency as you can.” With the hot-water drilling, once it starts, it continues to completion no matter what weather pops up. All other plans will undoubtedly change at some point and, when they do, he said, “you have to be able to work with that rather than fight against it and hope that you’ve got enough contingencies so that whatever happens you know what the next best thing to do is.”

Carl Robinson, the head of BAS Airborne Sensor Technology, sat down with us during our visit to show us the aerial work he had just completed over Thwaites. For seven days, his team camped out on the glacier and flew every day to map many different properties of the ice and rock below. They used a radar to map the internal layers of the ice sheet and the topography below it, a magnetometer to measure the magnetics, and gravitometer to measure the gravity of the material beneath the plane. Carl reported being very pleased to have had only one day of bad weather during this trip where the plane sat grounded all day. Their weather plan had contingencies that allowed for up to four.

Having just come out of the field from Thwaites Glacier, Carl Robinson shows footage of the glacier from the sky. From a Twin Otter airplane across six days of flight lines, he has helped to collect ten thousand kilometers of ice and bedrock measurements across the region (left to right: Tasha Snow, Elizabeth Rush, Jeff Goodell, Carl Robinson, and Carolyn Beeler). Photo credit: Linda Welzenbach

The ship spent three days at Rothera, the patient making it back to Chile to receive the medical help they needed, and a replacement marine tech onboard the ship, we headed back toward the Amundsen Sea. The Palmer moved westward at 13 knots, fast and furious for the aging icebreaker. Four days later we cruised quickly through sea ice, banded along the edge of the Amundsen Sea, that slowed us on our way from Thwaites to Rothera. We had needed to slow to three knots to break thick ice previously, but since our departure from Rothera, winds had moved the sea ice elsewhere to give us a nearly open corridor. On this day, at least, the weather worked in our favor.