In the field at last! TARSAN collects data at Thwaites Glacier

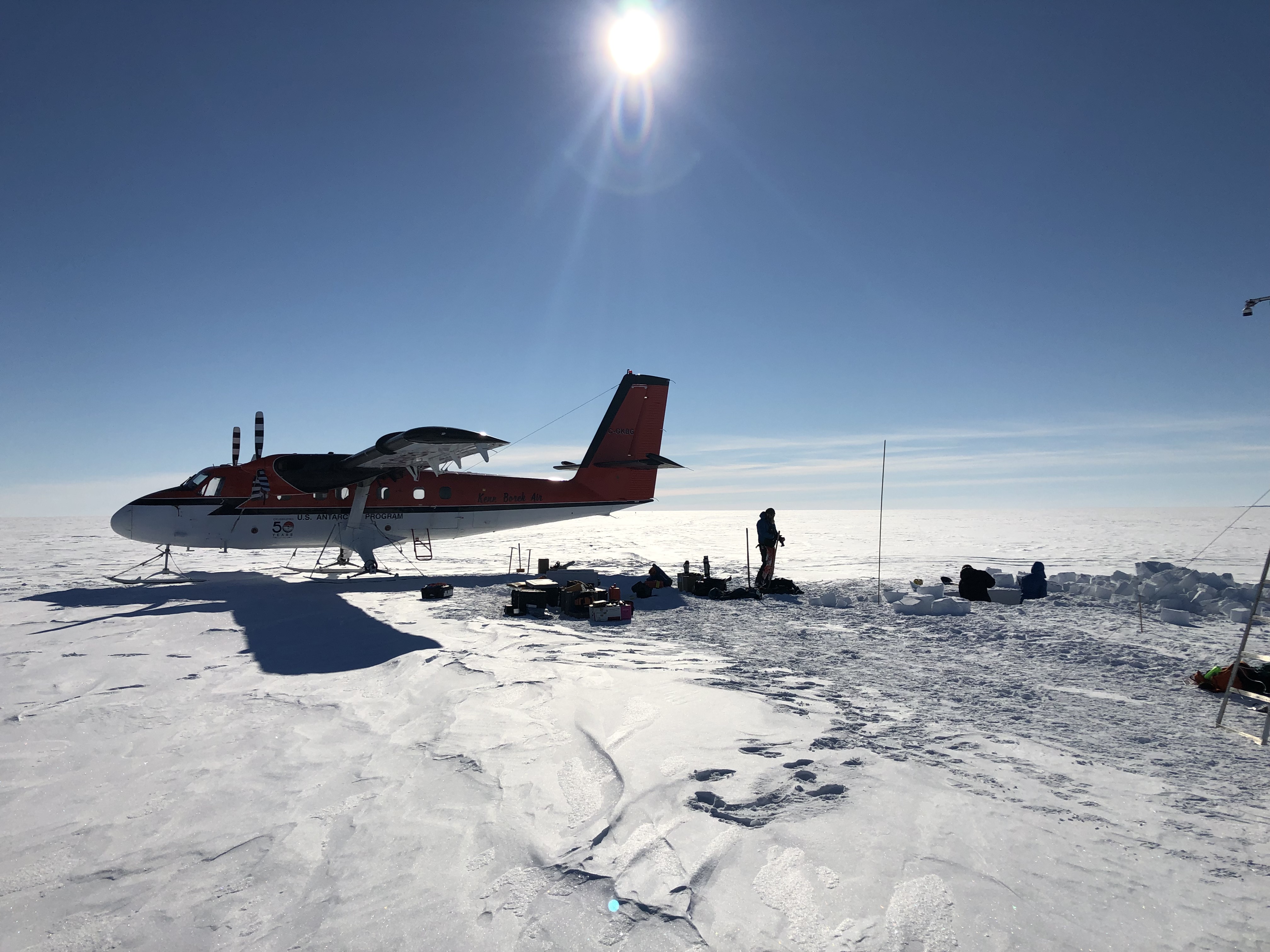

The TARSAN ice team swung into action quickly after arriving at WAIS Divide camp (Figure 1 above). WAIS Divide, located on the highest part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, was first opened in 2006 in support of a major ice coring effort to gather a record of past Antarctic and global climate data reaching back nearly 70,000 years. Since then, the camp has served as a logistical hub in support of additional work on the borehole, and for other science in the region. WAIS Divide camp is the gateway for the on-ice research on Thwaites Glacier conducted by ITGC scientists across our field seasons.

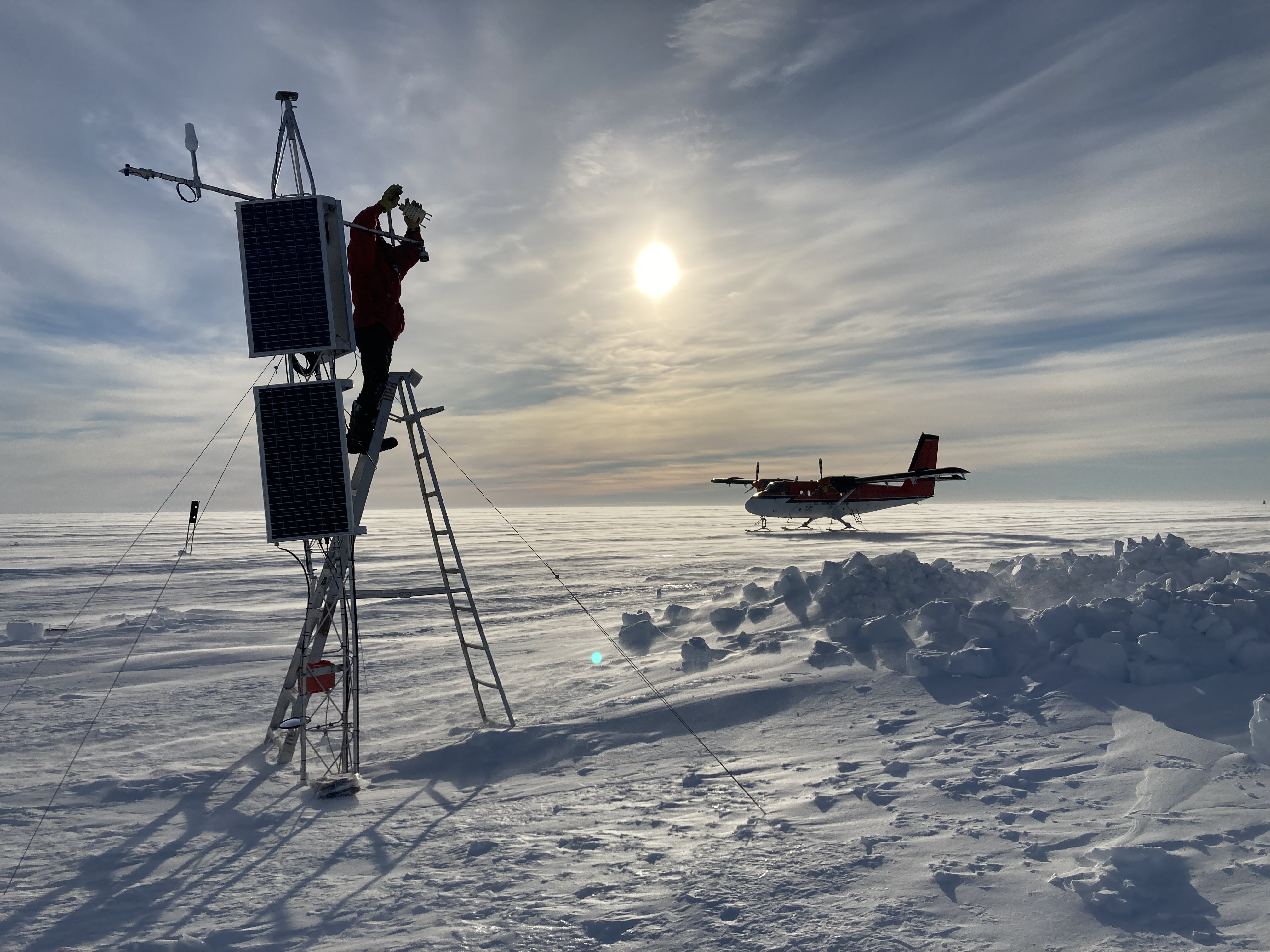

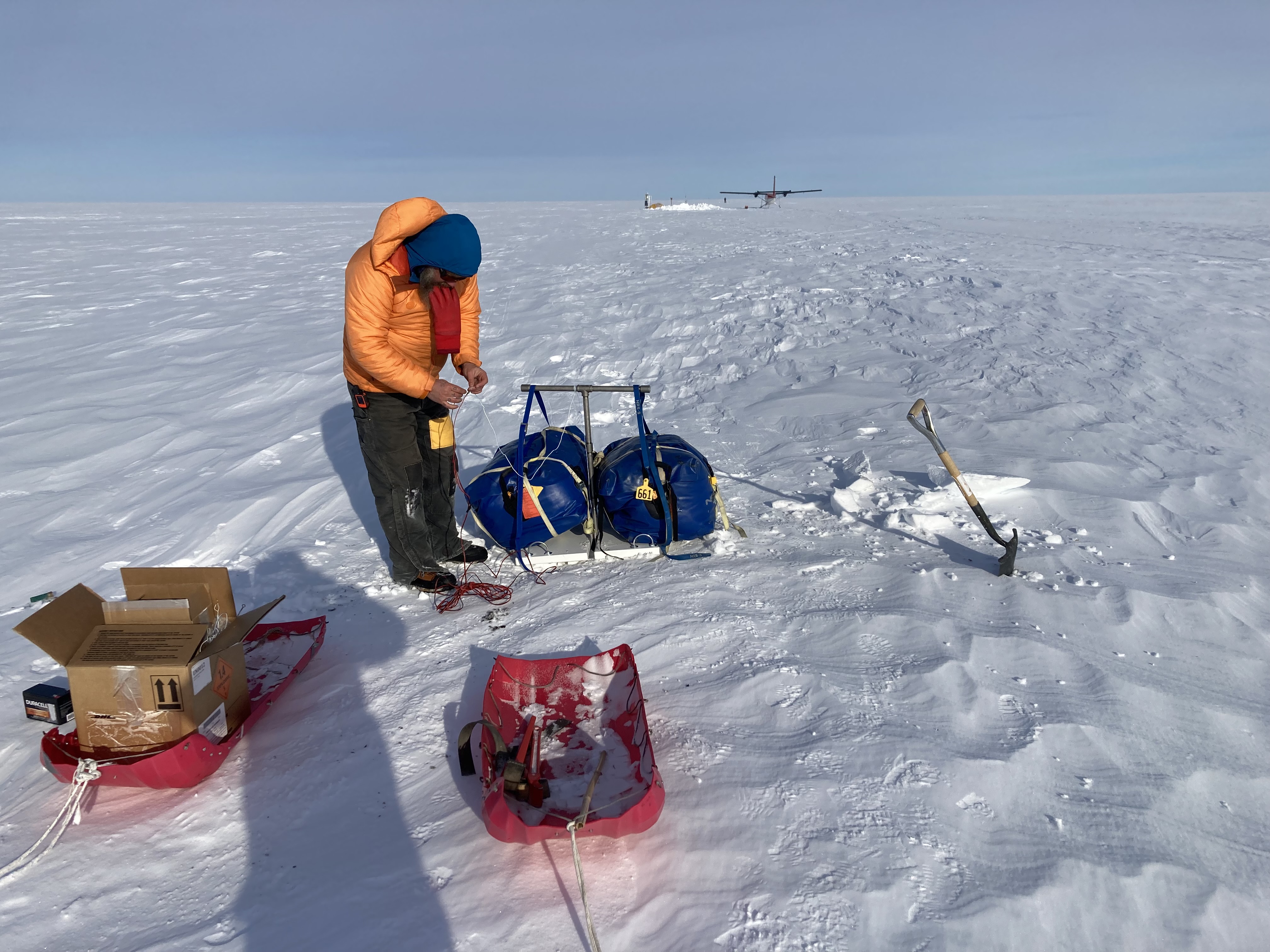

After some re-planning yet again, we designed our field work around three daytrips to the Thwaites Glacier and Dotson Ice Shelf areas, dividing the team differently each day between the two study sites to make the most out of the limited time we would have on the ground. We tested field instruments and repacked nearly every day to account for new tasks, plans, and unknown challenges (Figure 2 below).

Flying over the gigantic Thwaites Glacier outlet is awe-inspiring. First, the entire two-hour flight is over this single glacier, from its highest reaches near WAIS Divide camp to its outlet to the sea. The scale of the area that is breaking apart along the coastline, and the structures formed in the ice by calving, are mind-boggling. Thousands of broken plates of ice, each the size of a city block or more and thousands of feet thick, are scattered as far as the eye can see, spanning 60 miles or so (Figure 3 below).

Ted, Gabi, and Chris generally worked on the AMIGOS stations at the Cavity and Channel sites, with one team of pilots, and Christian and the other pilot team worked on Dotson most (Figure 4 below). The tasks at the AMIGOS sites were to assess the status of the AMIGOS and repair them if possible, and to recover two specialized radio echo sounders (ApRES) that were left running two years ago to monitor ice thinning and stretching. We also hoped to run a new experiment with an acoustically sensitive optical fiber that was part of the installation in the borehole two years ago. At Dotson, there were two additional ApRES instruments that had to be recovered, and some resurveys with the instruments on sites that were measured only briefly in the earlier field work.

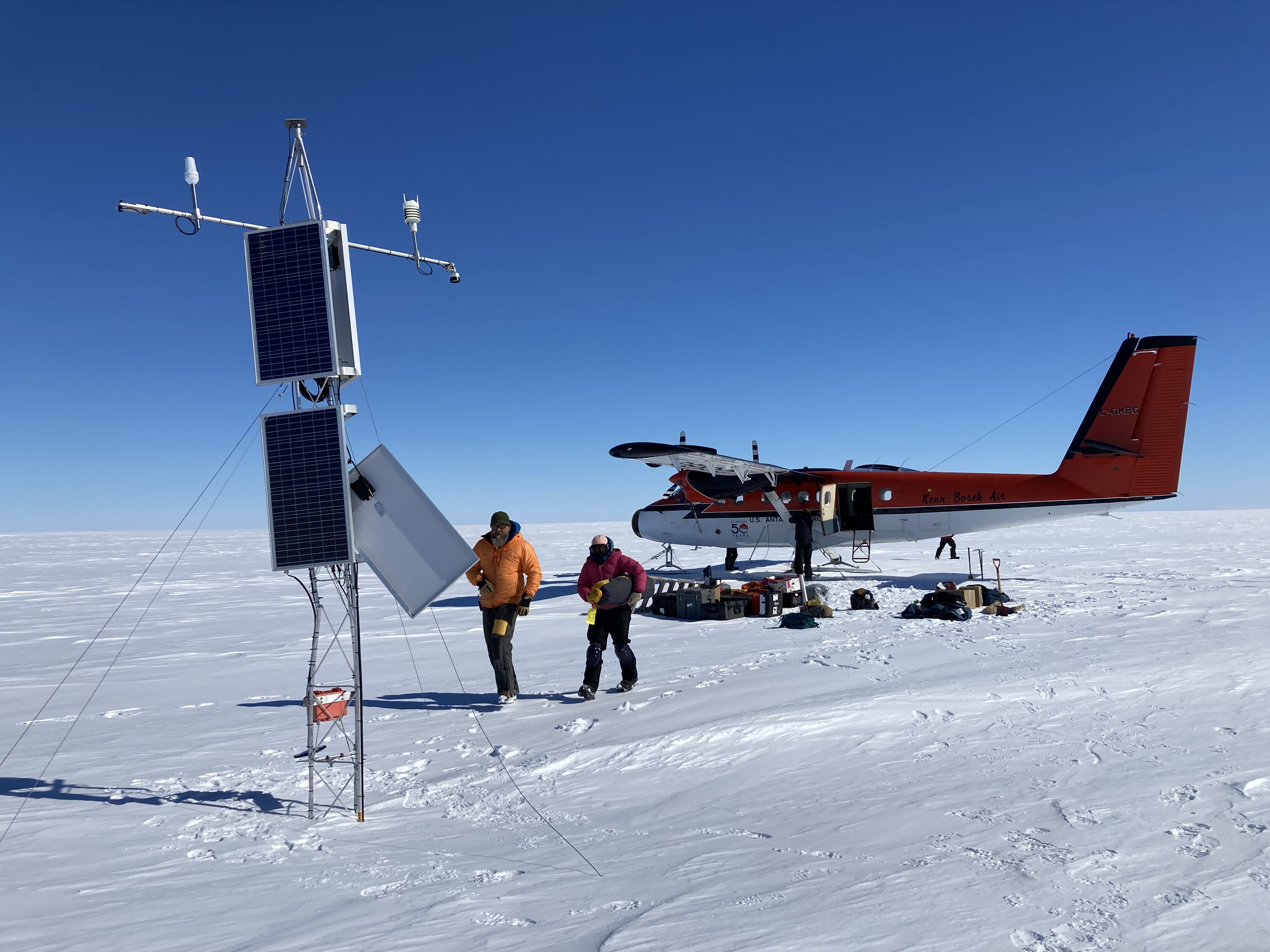

The AMIGOS stations had clearly taken a beating in the two years since they were installed (Figure 5 below). Both stations had had one solar panel ripped away by the howling wind, which at times had reached over 100 miles per hour according to its weather measurements. The station at Cavity was still operating, however, and had been sending a few data messages back to our warm offices at home over the satellite uplink. Channel AMIGOS did not appear to be functional, and so during that visit we focused on downloading the onboard data. Snow height measurement on the tower indicated that the ApRES instruments left at Channel would be nearly 5 meters, or 16 feet, below the surface; despite an 11-foot test pit looking for the top of the installation at Channel, we could not find it or recover it. At Cavity, a concerted effort finally extracted the unit at ~4.3m depth (13.5 feet; Figures 6 and 7 below) after a long day of snow mining. Further work on Cavity station successfully restored thermal profiling with the fiber optical cable and data file uploading. At both stations, we were also able to recover the most recent 40 days of ocean measurements directly from the cable linking them to the surface station, and the full archive of distributed thermal sensing (DTS) profile data – a huge trove of data that could not be sent over the satellite telemetry link. This data is derived from laser activation of three glass fibers that were installed through the borehole and into the ocean. The full data set provides temperature information every 25 cm (about a foot) for over 750 meters (~2400 feet) of cable in the ice and the ocean below.

One last push at Channel camp managed to gather acoustic data from a distributed acoustic sensing fiber (DAS) that was installed at both Channel and Cavity AMIGOS boreholes, as part of the same cable used for DTS measurements (a fourth strand of glass fiber sensitive to vibration). The Cavity AMIGOS strand was damaged near the surface – Channel was our only chance to make this experiment work. In addition to just listening for sounds within the ice, such as new fracturing or shear-related grinding, we set off small charges at Channel AMIGOS site to gather information on the structure of the ice and the ocean below. It worked, and a complex picture has emerged in the data that we will be evaluating in the weeks ahead (Figure 8 and 9 below).

The Dotson expeditions sought to extract two ApRES units left there in 2020 to monitor melting of the ice from warming ocean waters underneath, and to gather ice movement data from an area that showed unusual flow changes near a rock outcrop that cuts entirely through the floating ice plate. This movement, as tracked by satellite data, appeared to be linked to the rise and fall of the ocean tides. On the first visit, a GPS station was installed at a safe distance from the rock to gather data for several days. The team (Christian Wild and pilots) then flew to the ApRES site and found that the flags installed two years ago to mark the ApRES, and even top of one of the solar panels, still visible just above the surface and were quickly recovered. A team returned a few days later (Christian, Gabi, and pilots) to recover the GPS and visit several sites for repeat measurements to further identify key areas of melting at the ice base.

Overall, we had limited time on the ground, and needed to spend much more time troubleshooting with the AMIGOS to diagnose the problems with them, repair them, and download their entire data set (Figure 10 below). But we accomplished a tremendous amount in the three good weather days we had and will not return empty handed from this most remote place on our planet (Figure 11 below).